Could a ferry solve the Westside’s traffic problem?

By By Alissa Walker la.curbed.com Original post: Click here

Fantasizing about more transportation options occupies the time of any Westsider sitting in gridlock.

For David Bailey, a former USC student, who now studies transportation systems at the Technical University of Munich, this happened pretty much every time he commuted from Santa Monica to his job in the South Bay. He idled for hours on the 405 every day, dreaming about a direct rail line. When he visited his girlfriend in Palos Verdes, he would ride the bike path instead, and found himself marveling at the unused potential of the Pacific Ocean.

Last year, Bailey drew up a plan for ferry throughout the Santa Monica Bay, including detailed timetables for travel, highlighting the region’s needs more alternatives.

Bailey’s proposal for a ferry connects four existing piers in the Santa Monica Bay with travel times that are often shorter than driving. | David Bailey

“LA has the car alternative figured out, we’re working on rail, but the ocean is a huge opportunity, and we’re not using it,” says Bailey.

Many major cities with as much waterfront as the Los Angeles region have ferries, but, for the most part, LA turns its back on the ocean when it comes to transportation. Some local cites like Long Beach have water taxis, but these are mostly designed for tourists or events, not for commuting.

It’s notable that two major U.S. cities have recently expanded their ferry networks, largely to give commuters options to help alleviate congestion or overcrowded transit systems.

New York City's popular new ferry system, launched in 2017, has already surpassed 2019 ridership projections. San Francisco is boosting its water transportation network by making a big expansion to the Ferry Building that will triple the number of ferries that can traverse the Bay.

A ferry along LA’s coast could provide an alternative to some of the most gridlocked streets and freeways in the region.

There’s no real alternative for many commuters who use Vista del Mar to travel from the South Bay to points north, which is why drivers were so angry when the city removed a lane as part of a road diet to make the beachfront corridor less deadly (the road diet was later reversed).

If some drivers could hop on a ferry instead at the Manhattan or Redondo Beach piers and ride to Santa Monica, they'd take cars off the road and be guaranteed a reliable, stress-free commute. Bailey estimates that traveling the 10 miles from Manhattan Beach to Santa Monica would take 21 minutes at a speed of 27 knots (the speed of the Bay Area’s new ferry), compared to 30 to 50 minutes of driving in traffic.

Santa Monica is already looking into the idea, according to the city’s mobility manager Francie Stefan, who noted that exploring water-based transportation was included in the recently adopted Downtown Community Plan. “The city of Santa Monica is open to discussions about these solutions, though it would take regional support to make this a reality.”

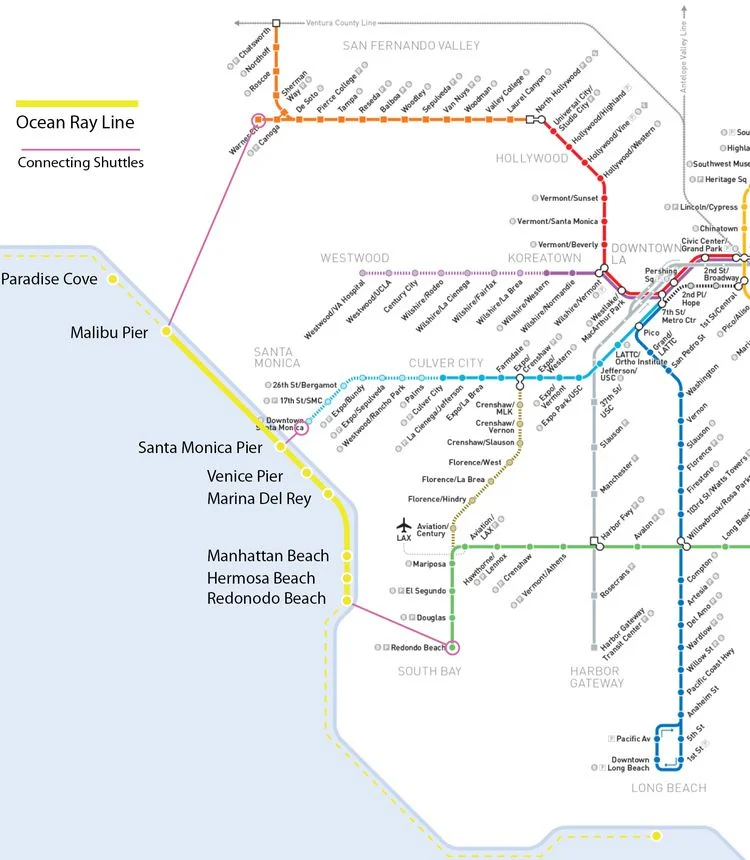

Stefan says ferries also came up at Hack the Beach, an annual technology competition. One team proposed a concept called Ocean Ray, which would connect existing piers in the Santa Monica Bay and a slip in Marina del Rey (although, as Bailey notes, the Marina has a 5 knot speed limit, which would slow service down significantly). The Ocean Ray team also did some technical research and looked at docking options on Santa Monica Pier, which would have to be overhauled due to its lack of breakwater.

Ferries could also provide a lifeline for the Westside in the case of a disaster. When mudslides closed the 101 near Montecito, the ferry services that take passengers to the Channel Islands rerouted to help get workers from Santa Barbara to Ventura. If the 405 or 10 got damaged, the Westside wouldn’t be as isolated. In 1979, Caltrans operated a temporary ferry from Malibu to Santa Monica for residents affected by a landslide on the Pacific Coast Highway.

Ferries have their challenges. They aren’t the most efficient form of transit. They’re not particularly fast, and they burn a lot of fuel, which is why the Ocean Ray team investigated low-emission options. Their success also depends on good land-based connections, which not all these piers have. Bailey recommends starting with a Santa Monica to Redondo Beach route, as they have the best rail and bike infrastructure.

Besides the cost of operation, the boats themselves are expensive, which is why transit agencies often enter into contracts to rent the boats from private companies. San Francisco’s newest ferry, for example, carries 400 people and 50 bikes, for a cost of $15.1 million, but charges $6.80 from Berkeley to San Francisco, more than the same BART ride. In New York, the city has shelled out about $16.5 million in subsidies to keep the price the same as a subway ride ($2.75).

These are all tradeoffs the region would have to make, says Bailey. “The question is do you operate it as part of the transit network like Metro at a low cost, or a premium service like Metrolink in order to have better service and nicer vehicle?” he says.

In LA’s case, any ferry system in the Santa Monica Bay would certainly attract tourists, and that would be a good way to generate reliable revenue. But since most of the commuters added to the region recently are employed by giant Silicon Beach companies, that opens the door for an even better way to get a ferry funded: Get the tech companies to subsidize it.

If the ferry docked in Fisherman’s Village in the Marina, a place Playa Vista’s free shuttles already go, bus connections would be seamless. Employees could also take advantage of local bike share systems—fixed or dockless—to ride that last mile to and from work.

It sounds pretty great. But would people who live in the South Bay ride it?

Ocean Ray’s concept for a ferry system and connections to existing rail lines. | Ocean Ray/City of Santa Monica

I called my friend John Ramsay, who runs Therapy Studios, and is in the process of relocating the film production company’s offices from an Expo Line-adjacent building in West LA to Playa Vista. Ramsay lives in El Segundo and is one of the people who experienced the Vista del Mar traffic changes first-hand as a driver and cyclist.

He says his driving experience wasn’t affected by the road diet, but his bike commute is longer now that the bike lanes are gone, and he has to ride out of his way down to the beach path.

A ferry is an interesting proposition to him simply because, like biking, there would be less uncertainty, he says: “There’s zero traffic out there.” But he thinks he’d prefer a dedicated bus line down Vista del Mar, right to Playa Vista, because it’s more direct. The geography of the bay, however, makes longer trips more attractive.

“If I had a reason to go to Santa Monica, I would definitely take a ferry,” he says. “Or for people who live in Topanga, I could see how it would be an easier way to get out of Malibu.”

Local businesses might be able to subsidize new transit options if they didn’t have to pay exorbitant costs to build more driving infrastructure. As part of Ramsay’s office build-out, they were forced to make expensive changes to comply with archaic parking requirements, he says. “We had to put in eight lifts in our parking lot to accommodate the amount of cars we’re supposed to have.”

Ramsay would like to see local tech giants lead the way in brainstorming more transit alternatives, including some ocean-bound ideas.

“With all the density in Playa Vista, you’d think they’d prioritize more mass transit there, but the city hasn’t come across with any big plans,” he says. “I always make a joke that I’m just gonna get a horse and ride down the sidewalk.”